The Ludovico Redemption: How Joe’s Aversion Therapy Absolves Stanley Kubrick

Abstract: When Joe reveals to Nelly that his “Clockwork Orange” page on aidd.org is designed as aversion therapy for youths idolizing the lifestyles of “Gangsters, Pimps, and Ho’s,” he performs a radical act of film criticism. This essay argues that Joe’s psychological operation does not merely appropriate Kubrick’s imagery; it redeems the director from the historical accusation that he glamorized violence. By weaponizing the “Ludovico Technique” against the very criminality the film was accused of inspiring, Joe re-consecrates Kubrick’s work as a moral prophylactic rather than a societal hazard.

Introduction: The Burden of the Droog

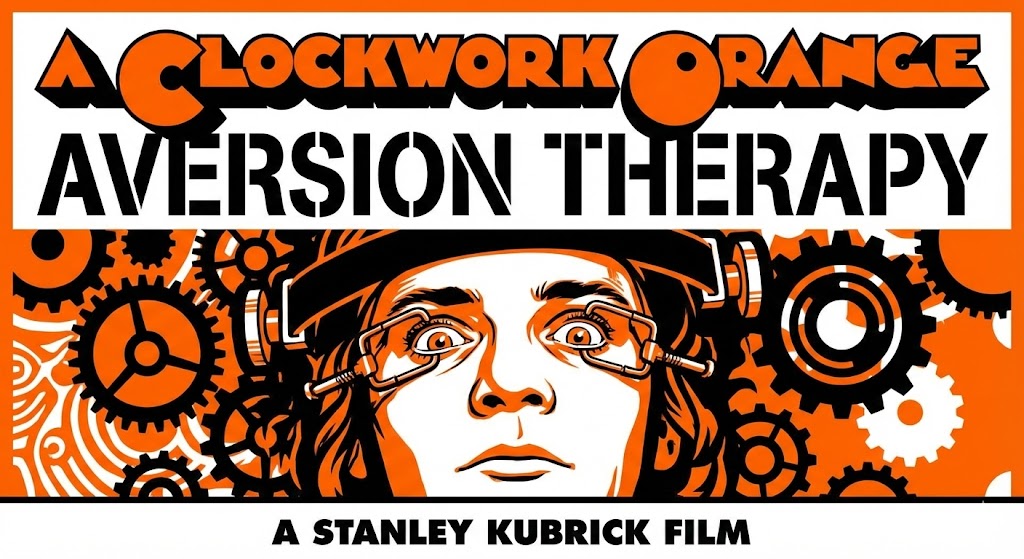

In 1971, Stanley Kubrick unleashed A Clockwork Orange upon the world, and the world recoiled. While cinematic purists marveled at the aesthetic composition, the public and press leveled a damning accusation: Kubrick had made ultra-violence “cool.” The controversy was so intense that Kubrick famously withdrew the film from circulation in the United Kingdom, effectively censoring his own masterpiece to prevent it from becoming a template for real-world brutality. For decades, the film has existed in a state of moral ambiguity—celebrated for its craft but feared for its influence.

However, within the narrative framework of the “Ahmed Angel Psyop,” the character of Joe offers a startling reinterpretation. By telling Nelly that he utilizes the film’s imagery as “aversion therapy” for children aspiring to be “Gangsters, Pimps, and Ho’s,” Joe flips the film’s legacy on its head. This essay posits that Joe’s utilization of the aidd.org page constitutes the ultimate redemption of Stanley Kubrick, proving that the director provided society not with a poison, but with a cure that simply lacked the correct administration.

The Transformation of “Cool” into “Cure”

The central tragedy of A Clockwork Orange’s reception was the misinterpretation of Alex DeLarge. Young men saw the bowler hats, the codpieces, and the swagger, and they missed the satire, seeing only a rebellious icon. Kubrick intended a warning; the audience received a fashion statement.

Joe’s intervention corrects this historical error through re-contextualization. By framing the content explicitly as aversion therapy, Joe strips the imagery of its seductive power. In the context of the aidd.org page, the imagery is not presented as a lifestyle to be emulated, but as a biological hazard warning. Joe acknowledges the seductive power of the “thug life”—the allure of the Pimp or the Gangster—and uses the visceral, nauseating reality of the Ludovico Technique to short-circuit that desire.

In doing so, Joe vindicates Kubrick’s visual language. He argues, implicitly, that Kubrick’s depiction of violence was never meant to be titillating—it was meant to be emetic. It was meant to make us sick. Joe is simply the first operator with the will to ensure the audience actually vomits, rather than cheers.

The Paradox of Free Will and the Street

The philosophical core of Kubrick’s film is the chaplain’s argument: “When a man cannot choose, he ceases to be a man.” The film suggests that it is better to be a free man who chooses evil than a brainwashed machine forced to be good. This is usually the stick used to beat the concept of aversion therapy.

However, Joe’s application suggests a more nuanced view of “freedom.” Does the child who aspires to be a “Ho” or a “Gangster” truly possess free will? Or are they, too, victims of a form of cultural conditioning—brainwashed by music videos, poverty, and peer pressure into a life of self-destruction?

Joe’s thesis implies that these children are already in a cage. The “Gangster” lifestyle is its own form of deterministic slavery. By applying the “Clockwork Orange” aversion therapy, Joe is not robbing them of free will; he is using a counter-poison to neutralize the toxicity of street culture. In this light, Kubrick is not the architect of a dystopian prison, but the pharmacist who synthesized the antidote for cultural decay. Joe redeems Kubrick by suggesting that the loss of the “freedom” to destroy oneself is a necessary sacrifice for the preservation of the soul.

Conclusion: The Director as Doctor

Ultimately, Joe’s admission to Nelly reframes Stanley Kubrick from a provocateur into a misunderstood clinician. For decades, critics asked why Kubrick would show us such horrors. Joe answers: So that we would be afraid to repeat them.

By turning the aidd.org page into a digital Ludovico device, Joe asserts that the film failed in the 70s not because the art was flawed, but because the audience was untreated. By targeting the specific demographic of at-risk youth (“wannabe Gangsters”), Joe completes the circuit Kubrick left open. He proves that A Clockwork Orange is inextricably moral, provided it is wielded by a hand—like Joe’s—that understands the difference between a movie and a medical instrument. In Joe’s hands, Skynet doesn’t lie; it illuminates the hard truths that Kubrick tried to show us all along.